Doubts are growing about the biosignature approach to alien hunting

By Elise Cutts | Published: 2024-11-16 18:00:00 | Source: Hard Science – Big Think

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

In 2020, scientists discovered a gas called phosphine in the atmosphere of a rocky planet the size of Earth. Knowing that phosphine can only be produced through biological processes, “scientists assert that something living now is the only explanation for the source of the chemical.” the New York Times I mentioned. With the transfer of “biosignature gases,” phosphine seemed like a success.

Until it wasn’t.

The planet was Venus, and the claim of a possible biosignature in Venus’ skies remains mired in controversy, even years later. Scientists can’t agree on whether or not phosphine is there, let alone whether it’s strong evidence of an alien biosphere on our twin planet.

What turned out to be difficult on Venus will be more difficult on exoplanets several light-years away.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which launched in 2021, has already sent back data on the atmospheric composition of a medium-sized exoplanet dubbed K2-18 b that some have interpreted – controversially – as possible evidence of the presence of life. But even as hopes for detecting biosignatures rose, some scientists began to publicly question whether gases in an exoplanet’s atmosphere would be convincing evidence of alien life.

A large body of recent research explores the enormous uncertainties in exoplanetary biosignature detection. One of the main challenges they identify is what a philosopher of science is Peter Vickers At Durham University Invites The problem of unstudied alternatives. Quite simply, how can scientists be sure that they have ruled out all possible non-biological explanations for the presence of gas, especially since exoplanetary geology and chemistry are as mysterious as alien life?

“New ideas are being explored all the time, and there could be an abiotic mechanism for this phenomenon that has not yet been conceived,” Vickers said. “This is the problem of unimagined alternatives in astrobiology.”

“It’s a small part of that elephant in the room,” the astronomer said. Daniel Angerhausen From the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, he is a project scientist on the LIFE mission, a proposed space telescope to search for biosignature gases on Earth-like exoplanets.

If or when scientists discover a hypothesized biosignature gas on a distant planet, they can use a formula called Bayes’ theorem to calculate the chance of life existing there based on three possibilities. Two have to do with biology. The first is the probability of life appearing on this planet given everything that is known about it. The second is the possibility that, if life existed, it would create the biosignature that we observe. Both factors carry a great deal of uncertainty, according to astrobiologists Cole Mathis From Arizona State University and Harrison Smith From the Institute of Earth and Life Sciences of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, which explored this type of thinking in paper Last fall.

The third factor is the possibility that a lifeless planet could have produced the observed signal, an equally serious challenge, as researchers now realize, and intertwined with the problem of unimagined abiotic alternatives.

“This is the possibility where we say you can’t hold the job responsibly,” Vickers said. “It can range from almost anything from zero to 1.”

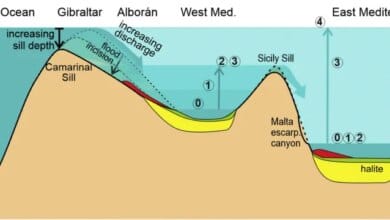

Consider the case of K2-18 b, a “mini-Neptune” intermediate in size between Earth and Neptune. In 2023, data from the James Webb Space Telescope revealed a statistically weak sign of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) in its atmosphere. On Earth, DMS is produced by marine organisms. Researchers who It was initially discovered in K2-18 b They interpreted other gases detected in its skies to mean the planet is a “water world” with a habitable surface ocean, supporting their theory that the DMS there comes from marine life. But other scientists interpret the same observations as evidence of a gaseous, inhospitable planetary formation similar to that of Neptune.

Unstudied alternatives have forced astrobiologists several times to revise their ideas about what makes a good biosignature. When the phosphine It was discovered on the planet VenusScientists did not know any way by which it could be produced in a lifeless rocky world. Since then, they have identified several possible options Abiotic sources of gas. One scenario is that volcanoes release chemical compounds called phosphides, which could react with sulfur dioxide in Venus’ atmosphere to form phosphine, a plausible explanation given that scientists have found evidence of active volcanoes on our twin planet. Likewise, oxygen was considered a biosignature gas until 2010, when researchers, including Victoria Meadows, at NASA’s Astrobiology Institute’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory He started to find Knock That rocky planets can Oxygen accumulates Without the biosphere. For example, Oxygen can be formed From sulfur dioxide, which is abundant on worlds as diverse as Venus and Europe.

Today, astrobiologists have largely abandoned the idea that a single gas can have a biosignature. Instead, they focus on identifying “clusters,” or groups of gases that cannot coexist without life. If there is anything that can be called the standard biosignature today, it is the combination of oxygen and methane. Methane decomposes rapidly in oxygen-rich atmospheres. On Earth, the two gases coexist only because the biosphere constantly replenishes them.

Until now, scientists have been unable to come up with an abiotic explanation for the biosignatures of oxygen and methane. But Vickers, Smith and Mattis doubt that this particular pair — or perhaps any combination of gases — will be convincing at all. “There is no way to be sure that what we are looking at is actually the result of life, and not the result of an unknown geochemical process,” Smith said.

“The James Webb Space Telescope is not a life detector,” Mattis said. “It is a telescope that can tell us what gases are in a planet’s atmosphere.”

Sarah Roheimeran astrobiologist at York University who studies the atmospheres of exoplanets, is more optimistic. She is actively searching for alternative abiotic explanations for the biosignatures of groups such as oxygen and methane. However, she says, “I would open a bottle of champagne — which is very expensive champagne — if we saw oxygen, methane, water and carbon dioxide.”2“On an exoplanet.

Spilling drinks on an exciting finding in private is, of course, different from telling the world they’ve found aliens.

Röheimer and the other researchers they spoke to Quantities In this story they question the best way to talk publicly about uncertainty about biosignatures, and they ask how fluctuations in astrobiological opinion about a particular discovery can undermine public trust in science. They are not alone in their concern. As the Venusian phosphine saga moves toward its climax in 2021, NASA managers and scientists are imploring the astrobiology community to set consistent standards for certainty in detecting biosignatures. In 2022, Hundreds of astrobiologists gathered For a virtual workshop to discuss this issue – although there is no official standard for a biosignature or even a definition. “Right now, I’m very happy that we all agree, first and foremost, that this is a small problem,” Ungerhausen said.

Vickers says research is moving forward despite the uncertainty, as it should. Hitting a dead end and having to backtrack is normal for an emerging field like astrobiology. “This is something people should try to understand better about how science works in general,” Smith said. “It’s okay to update what we know.” Smith and Vickers say that bold claims about biosignatures have a way of fanning the flames of scientists falsifying them as they search for unstudied alternatives.

“We still don’t know what’s going on on Venus, so of course we’re desperate,” said astrochemist Clara Souza Silva of Bard College, an expert on phosphine who helped discover Venus. For her, the next step is clear: “Let’s think about Venus again.” Astronomers have practically ignored Venus for decades. The biosignature controversy has sparked new efforts not only to discover previously unconsidered abiotic sources of phosphine, but also to better understand our sister planet itself. (at least Five missions to Venus It is scheduled to be planned in the coming decades.) “I think this is also a source of hope for exoplanets.”

this condition Originally appeared on Nautilusa scientific and cultural magazine for curious readers. Sign up for Nautilus Newsletter.

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ