How will Europa Clipper place cameras on a distant icy moon?

How will Europa Clipper place cameras on a distant icy moon?

By Paige Colley | MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) | Published: 2024-10-31 17:00:00 | Source: Hard Science – Big Think

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

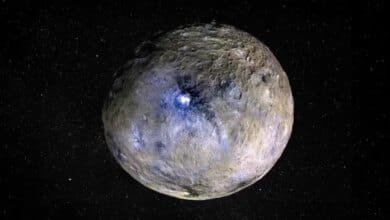

With the successful launch of its latest space mission, NASA is set to return to conduct a close-up investigation of Jupiter’s moon Europa. In mid-October, the Europa Clipper lifted off on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket on a mission that will take a closer look at… Europe’s icy surface. Five years from now, the spacecraft will visit the Moon, which has a water ocean covered by an icy water crust. The spacecraft’s mission is to learn more about the composition and geology of the Moon’s surface and interior and assess its astrobological potential. Because of Jupiter’s intense radiation environment, Europa Clipper will make a series of flybys, with its closest approach coming within just 16 miles of Europa’s surface.

A research scientist in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Jason Soderblom is a research associate on two of the spacecraft’s instruments: the Europa Imaging System and the Europa Mapping Imaging Spectrometer. Over the past nine years, he and his fellow team members have built imaging and mapping tools to study Europa’s surface in detail to gain a better understanding of previously seen geological features, as well as the chemical composition of the materials present. Here it describes the basic plans and objectives of the mission.

Q: What do we currently know about the surface of Europa?

A: We know who NASA Galileo mission The data suggests that the surface crust is relatively thin, but we don’t know how thin. One of the goals of the Europa Clipper mission is to measure the thickness of that ice crust. The surface is littered with fractures that indicate tectonics is actively reemerging the Moon. Its crust is composed primarily of water ice, but there are also exposures of non-ice material along these cracks and ridges that we believe contain material coming from within Europe.

One of the things that makes examining surface materials more difficult is the environment. Jupiter is an important source of radiation, and Europa is relatively close to Jupiter. This radiation modifies materials on the surface; Understanding radiation damage is a key element to understanding the composition.

This is also what drives the scissor-style mission and gives the mission its name: we crisscross Europa, collect data, and then spend most of our time outside of the radiation environment. This gives us time to download and analyze the data and make plans for the next flight.

Q: Was this a big challenge when it came to designing the tools?

A: Yes, that’s one of the reasons we’re back now to do this job. The concept for this mission came around the time of the Galileo mission in the late 1990s, so it has been nearly 25 years since scientists first wanted to carry out this mission. We spent a lot of time figuring out how to deal with the radiation environment.

There are a lot of tricks that we have developed over the years. The tools are heavily shielded, and a lot of modeling went into working out exactly where to put this shielding. We have also developed very specific data collection techniques. For example, by taking a whole set of short observations, we can look for the signature of this radiative noise, strip away the bits of data here and there, add the good data together, and end up with a low radiative noise observation.

Q: You are engaged in two different visualization and mapping tools: European imaging system (EIS) and Imaging spectrometer mapping of Europe (Miz). How do they differ from each other?

A: The EIS primarily focuses on understanding the physics and geology driving processes at the surface, and looks for: fractured zones; Areas we refer to as chaos terrain, where icebergs appear suspended in a mass of water and mixed, mingled and twisted; Areas where we think the surface is colliding and subduction occurs, so one section of the surface is going under the other; Other areas spread out, so a new surface is created such as mid-ocean ridges on land.

The primary function of the MISE spectrometer is to constrain the surface composition. In particular, we’re really interested in sections where we think liquid water has reached the surface. It is also important to understand the material coming from within Europe and the material being deposited from external sources, separating that is necessary to understand the composition of that coming from Europe and using that to learn about the composition of the subsurface ocean.

There is an intersection between these two things, and that is my interest in the task. We have color imaging with our imaging system that can provide a preliminary understanding of composition, and there is a mapping component to our spectrometer that allows us to understand how the materials we are discovering are actually distributed and relate to geology. So there is a way to examine the intersection between these two disciplines – to extrapolate the compositional information derived from the spectrometer at much higher resolution using the camera, and to extrapolate the geological information we learn from the camera to the compositional constraints from the spectrometer.

Q: How do these mission goals align with the research you conduct here at MIT?

A: One of the other major missions I was involved in was the Cassini mission, where I worked primarily with the spacecraft Vision and Infrared Spectrometer Team To understand the geology and composition of Saturn’s moon Titan. This instrument is very similar to the MISE instrument, both in terms of function and in terms of scientific purpose, and thus there is a very strong relationship between it and the Europe Clipper mission. For another mission, in which I lead the imaging team, I’m working on retrieving a sample of the comet, and my primary task in that mission is to understand the geology of the comet’s surface.

Q: What are you most excited about learning from the Europa Clipper mission?

A: I’m very fascinated by some of these very unique geological features that we see on the surface of Europa, and understanding the composition of the material involved, and the processes that drive those features. In particular, the chaotic terrain and fractures that we see on the surface.

Q: It will take some time before the spacecraft finally reaches Europa. What work needs to be done in the meantime?

A: A key component of this mission will be laboratory work here on Earth, expanding our spectral libraries so that when we collect a spectrum from Europa’s surface, we can compare it to laboratory measurements. We are also developing a number of models that allow us, for example, to understand how matter processes and changes starting in the ocean and then working its way through cracks and eventually to the surface. Developing these models is now an important part before we collect this data, and then we can make corrections and get improved feedback as the mission progresses. The optimal and most efficient use of spacecraft resources requires the ability to reprogram and optimize observations in real time.

Republished with permission MIT News. Read Original article.

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ