Scientists have found a record number of high-energy cosmic ray electrons, but the origin remains elusive

Scientists have found a record number of high-energy cosmic ray electrons, but the origin remains elusive

By Don Lincoln | Published: 2024-12-31 15:05:00 | Source: Hard Science – Big Think

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

Earth is under attack – not by humanity or rampaging aliens, but by the universe itself. Colossal cosmic forces disintegrate hydrogen atoms and catapult their components across the universe at nearly the speed of light. Some of these interstellar projectiles collide with Earth’s atmosphere, allowing sensitive detectors to reveal their secrets. A Modern measurement He studied the effects of extremely high energy and simultaneously settled an ongoing scientific debate while baffling scientists.

The constant deluge of radiation from space is called cosmic rays, and it consists mostly of two components: protons and electrons. Protons come from the center of atoms, while electrons are located at the periphery of atoms. Both can be accelerated by a variety of cosmic sources – from supernovas to colliding neutron stars – and (most commonly) by electric and magnetic fields found in outer space. These fields can propel protons and neutrons to very high speeds.

Since the 1930s, scientists have known about cosmic rays that hit the atmosphere, causing a series of particles to be detected on the Earth’s surface. Most of the high-energy cosmic rays that have been studied are protons. This is because protons are about 2,000 times heavier than electrons, which means that when a proton is moving, it is more difficult to deflect it than it is to deflect an electron. An appropriate analogy might be that protons behave like bowling balls, while electrons behave like ping-pong balls.

Because of this difference in how the two particles travel through space, very high-energy electrons can be scattered and lose energy. This means they can’t get very far, at least astronomically speaking. Therefore, higher energy electrons must have been created in our cosmic neighborhood.

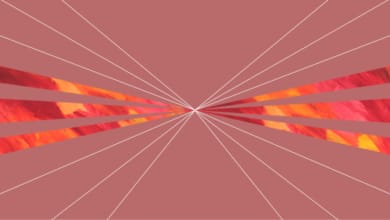

A recent measurement by the HESS Observatory of the energy spectrum of cosmic ray electrons has shown surprising results. Credit: F. Aharonian et al. (HESS Collaboration) (1); NASA Goddard; Adapted by APS.

Hess Observatory (High energy stereo system) is located in Namibia. It consists of four giant telescopes, each with a diameter of 12 metres, and one much larger telescope with a mirror diameter of 28 metres. Every night, you look up at the midnight sky, looking for flashes of light created when cosmic rays hit Earth’s atmosphere. It began operations in 2003, with upgrades being made in the intervening years. Most Recent paper It is based on 12 years of HESS observations between 2003 and 2015.

HESS trained its analysis software to distinguish between different characteristics of optical flashes left behind by protons and electrons in the atmosphere. Their latest paper focused on electrons. Previous measurements have measured the energy of cosmic ray electrons at just over a trillion electron volts of energy. (For comparison, the energy of electrons in TVs in the 1990s was more like 10,000 MeV, and the highest-energy man-made electron beam had an energy of 0.1 trillion MeV.) The recent HESS measurement observed electrons with energy up to 40 TeV.

Previous measurements had observed that low-energy electrons were more common than high-energy electrons, with a gradual decline. However, at an energy of about 1 trillion electron volts, the energy drops off sharply. This is thought to reflect the difficulty of high-energy electrons traveling very large distances. It’s like trying to shine a bright light through the fog. It can only get so far.

Previous measurements also indicated an unexplained excess of electrons with an energy of about 4 trillion electron volts. This excess was exciting to scientists, because it could serve as a signature of a theoretical form of matter called… Dark matter. Dark matter has not been observed directly, but it is thought to be five times more widespread than the normal matter of atoms. Scientists have been searching for experimental confirmation of dark matter for half a century, and observing it would be a real coup.

However, the HESS data is more precise than previous measurements and shows no signs of a 4 trillion electron volt surge, effectively dashing the dreams of those scientists who thought they had finally seen dark matter.

However, the behavior Hess observed is puzzling. These high-energy electrons must have formed relatively nearby, for example, within a few thousand light-years. This distance is much smaller than the size of the Milky Way Galaxy, which has a diameter of about 100 thousand light-years.

The data recorded by HESS does not appear to come from many sources, but rather favors a single, nearby origin. However, so far, the data doesn’t seem to be coming from any favorable direction, which is what one would expect if there was a single star in the cosmic neighborhood generating high-energy electrons.

The fact that these electrons are very high energy means that other competing experiments are not well suited to seeing them. However, Recent HESS measurement It only used data collected before late 2015. In the intervening years, HESS has been operational, with improved electronics, suggesting that future analysis may be able to pinpoint the source of this nearby cosmic cannon of electrons.

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ