The world’s largest library of lies contains good news about fake news

The world’s largest library of lies contains good news about fake news

By Bianca Giacobone, Guido G. Beduschi | Published: 2025-10-13 20:44:00 | Source: High Culture – Big Think

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

In 2011, Earl Havens, director of the Virginia Fox Stern Center for the History of the Book in the Renaissance at Johns Hopkins University, had a mission: He needed to convince his alma mater to purchase “an enormous collection of forgeries.” The collection, known as the Bibliotheca Fictiva, consists of more than 1,200 literary forgeries spanning centuries, languages, and countries—beautifully bound manuscripts bearing black-ink annotations purportedly written by Shakespeare; works written by Sicilian tyrants, Roman poets, and Etruscan prophets; Poems by famous priests and theologians, all partially or completely fabricated.

It was an unusual task for a researcher dedicated to the study of truth, but Havens was persistent. “We have never needed a collection like this more than we do now,” he told the dean of the libraries at the time. The Internet and the growing popularity of social media have changed how information is written, disseminated and consumed, giving rise to the phenomenon of fake news as we know it now. In such a “crazy, rapid-fire world of information,” the collection of ancient lies and distortions of facts contained in “Bibliotheca Fictiva” can offer guidance on how to navigate the moment, demonstrating that “what is happening now has, in fact, been happening since the invention of language and writing,” Havens said.

His plan was successful. Johns Hopkins University acquired the collection for an undisclosed sum and placed it in a wood-panelled library room at the Evergreen Museum and Library, a 19th-century mansion in Baltimore.

The sellers were Arthur and Janet Freeman, two book dealers who made their names in the world of antiquarian booksellers collecting fine forged literary works. Their project began in 1961, when Arthur Freeman, then a graduate student in Elizabethan drama at Harvard, began obtaining sources on John Payne Collier. Collier, a highly respected 19th-century scholar, caused a stir among his contemporaries when he claimed to have found thousands of annotations for a copy of Shakespeare’s Second Folio, which he said was written by one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries—but in fact Collier had forged it himself.

In the decades that followed, Freeman, who died in 2025, amassed an extensive collection of fake literature, collecting books whose contents were inherently deceptive. These included poems purportedly written by Martin Luther, who was not much of a poet, or accounts of Pope Joan, a medieval woman who disguised herself as a man and was elected pope, only to be arrested when she suddenly gave birth in the middle of a procession in Rome. The latter myth persisted for centuries and was not conclusively debunked until the 17th century.

Since Johns Hopkins University acquired the collection, Havens and other professors have used these works to teach students about media literacy and misinformation. This is a relatively recent development in academia, where scholars have mostly ignored the history of forgery. “Over time, the light bulb goes off in this information environment, and people go back to the past to learn things about misinformation and fakery that are very relevant today,” Havens said. “And it’s kind of comforting to know that this isn’t just a phenomenon in today’s digital social media environment.”

One of the most important things students can learn from the group is not only the ability to recognize whether the content of a text is correct or not, but that writing is often created with a purpose behind it. Shiner Ehim, a liberal arts graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, where she attended Havens’ summer seminar, said this gave “more clarity and clarity” to her approach to consuming news and information.

“I shifted my focus from ‘Is this true?’ to ‘Who created this?’ Who benefits from this, and why? What are they trying to do? What are they trying to exploit?’” She said. “When I hear news that sounds suspicious, I ask myself: What fear, what desire, what cultural anxiety is this story exploiting?” There is always a reason for that.

For example, the reasoning behind the Gift of Constantine, perhaps the most significant forgery in the history of Western culture, is clear. The 8th-century false edict claimed that the Roman Emperor Constantine gifted the western part of the Roman Empire to the pope, and was used by the papacy for centuries to bolster its claims to political power—until the edict was debunked in 1440 by the humanist scholar Lorenzo Valla.

For Ehim, reading ancient travelogues containing apocryphal accounts of journeys to distant lands, inhabited by people described as “curious or savage,” made her realize how powerful and harmful narratives can be. “These fairy tales became the blueprint for the transatlantic slave trade,” she said. “Imagination has come true, and that’s a scary thing.”

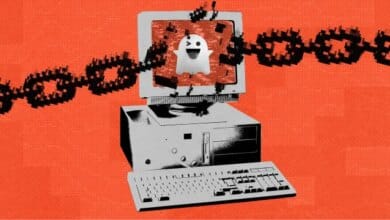

The information environment has certainly changed radically since the time of Constantine’s donation or travelogues, and it is now going through two particularly turbulent decades. Kirsten Eddy, a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center who specializes in news and information habits, points out that the Internet and social media have changed people’s attitudes toward information.

“People are exposed to more information from more sources than ever before,” Eddy said. “Not only is it difficult for people to know what to trust, but they also feel increasingly fatigued by or even avoid the news.” In the United States, public trust in major organizations and news media has declined steadily in the 21st century, with trust in national news organizations in particular declining over the past decade, according to a US State Department report. Pew Research Center.

The spread of generative AI is likely to exacerbate this moment of doubt. Recent report Through fact-checking site NewsGuard, it found more than 1,200 websites producing unreliable news generated by artificial intelligence “with little to no human oversight.” “People’s confidence in their abilities to identify fake or AI-generated information is not widespread,” Eddy said.

Generative AI has the potential to shake up “the foundations of how text is generated,” and reduce “our trust in the written word,” in general, Thomas Hellström, who leads the intelligent robotics group at Umeå University in Sweden, hypothesized in a recent paper.

However, another way to look at it is that AI is the latest tool in humanity’s long history of shaping and distorting narratives. Damien Charlotin, a researcher at HEC Paris and Sciences Po, where he studies big language models, law and disinformation, points out that in the legal context, there are cases where artificial intelligence has created fake legal cases that are used to support legal arguments.

“But in the legal field, playing fast with the authorities, forging and pasting a series of citations, falsifying and undermining arguments in bad faith, is something that always happens,” he added. “What has changed is that, because we have this new tool that can create things that don’t even exist, we can now easily spot bad and negligent lawyers.”

But bad lawyers, with their bad arguments, existed before AI, too, just as the human tendency to lie, fake, and falsify texts existed before we coined the term “fake news,” as reported in Bibliotheca Fictiva. He bears witness.

In 2024, Havens and Christopher Celenza, dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences at Johns Hopkins University, will host a conference Virtual seminar On the history of misinformation.

“The scale and speed of change we are seeing in the media is unprecedented in human history,” the university said books In the description of the symposium. “Yet in the past, people faced moments of crisis—moments when writing seemed unreliable, when the form of written information changed, and when new forms of publication forced a reassessment of the nature of truth.”

In these perilous moments, it is worth remembering that humanity’s record of overcoming these moments is promising. Accumulated expertise, of the kind found in libraries, universities, government agencies, and scientific institutions, tends to be on the winning side. The question today is whether this expertise can keep up with the speed and scale of deception — and to what extent the public will keep up, too.

“There will be crazy theories, there will be people peddling conspiracies, and there will be errors.” – Celenza He said. “But hopefully, over time, if we can stick together, we will realize that the combined experience is still something we have to fight for.”

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ