Lung cancer vaccine heading to trial: How does it work?

Lung cancer vaccine heading to trial: How does it work?

By Tim Brinkhof | Published: 2024-12-12 15:52:00 | Source: Health – Big Think

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

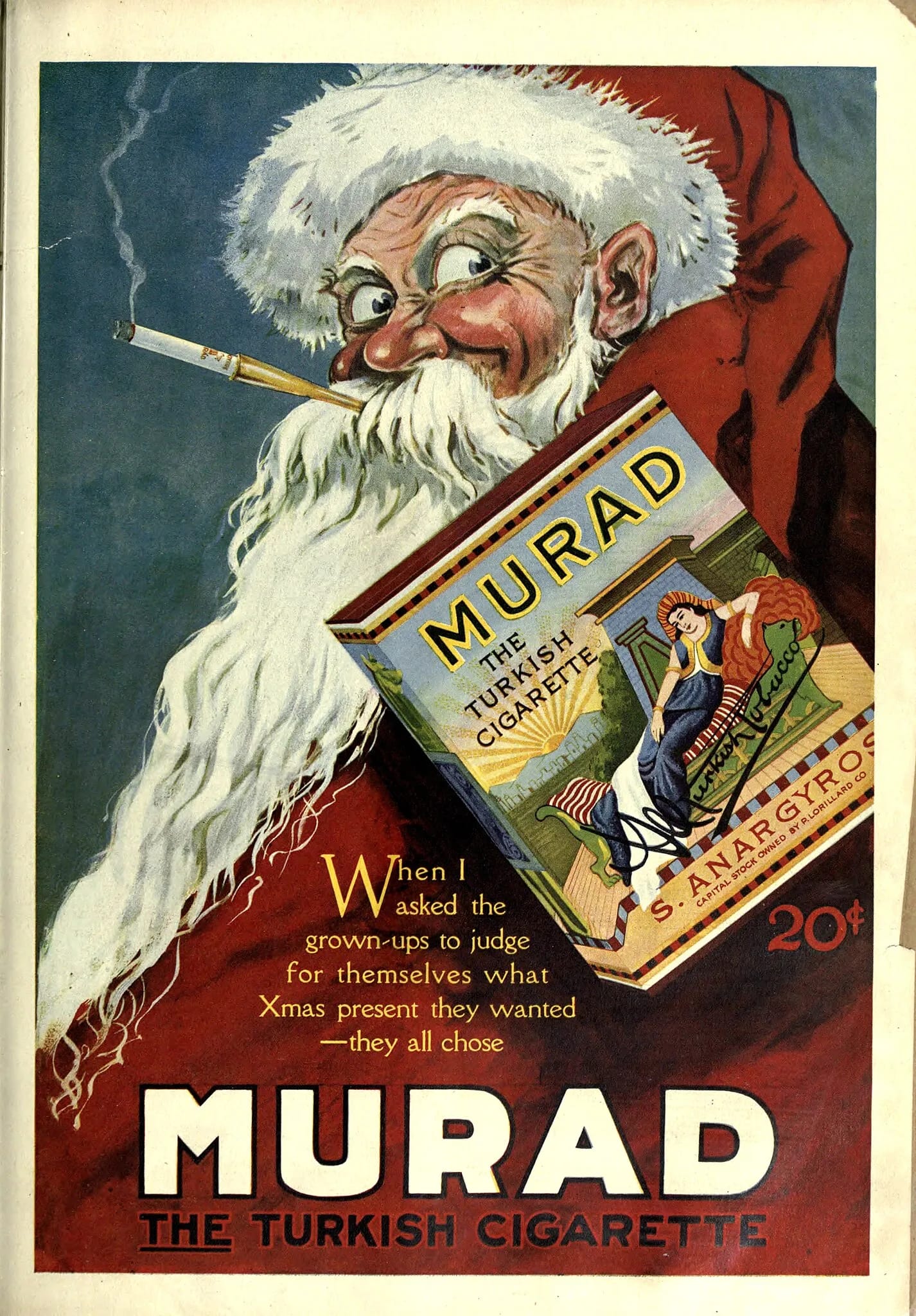

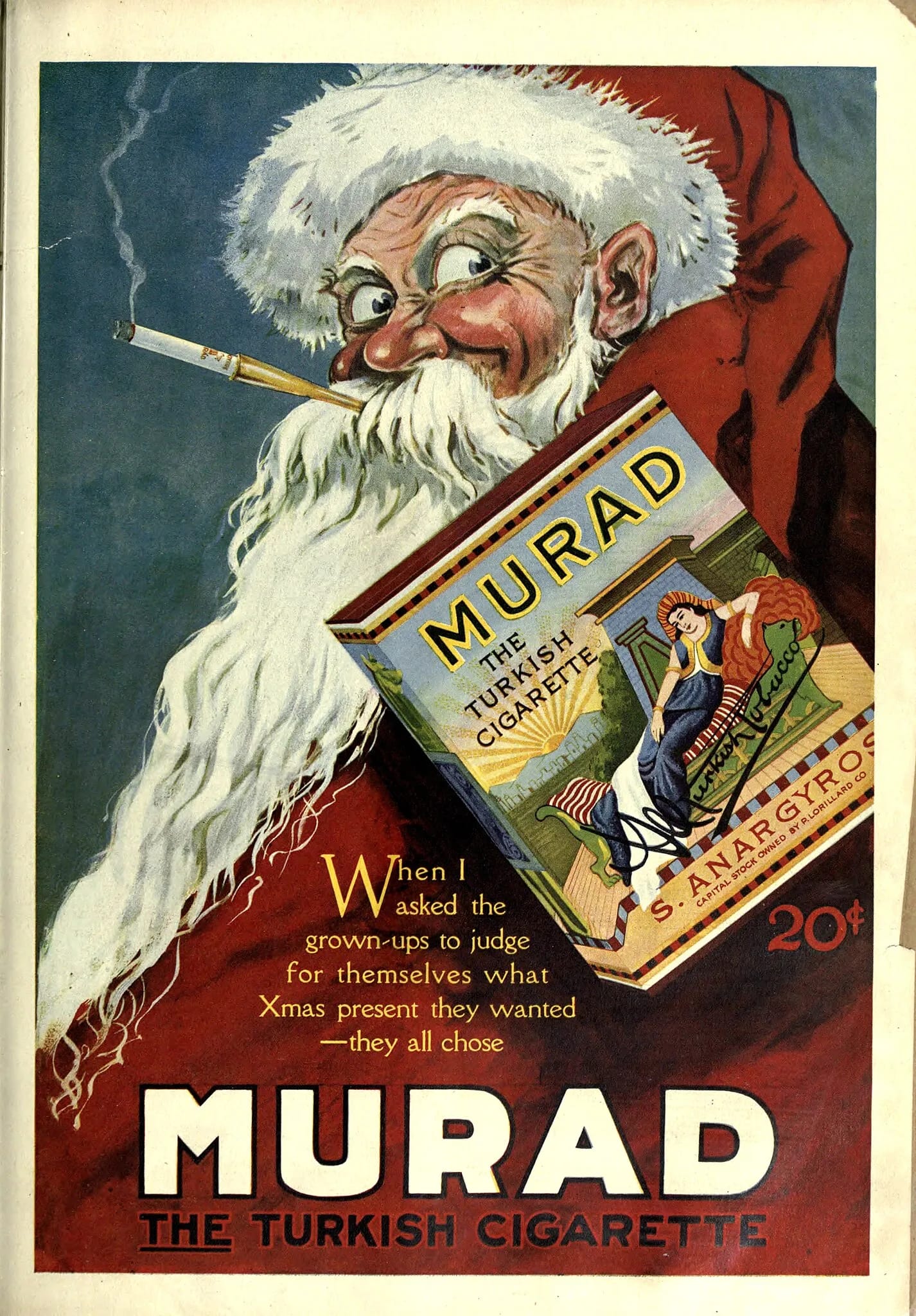

For much of human history, people believed that smoking tobacco was perfectly healthy. Native American tribes, who introduced the tobacco plant to Europeans — and thus the rest of the world — used it for cultural and spiritual purposes, and gave little thought to its long-term effects on the human body.

Meanwhile, Vintage ads From the early 1900s it was claimed that smoking provided a variety of health benefits, from relieving stress and anxiety to helping treat indigestion, weight gain, depression, and even respiratory infections. In addition, Big Tobacco has often partnered with doctors and other health professionals to lend an additional air of credibility to such claims.

Interestingly, this unexpected partnership was itself a response to a growing body of research that presented the now universally known fact that smoking actually leads to serious, often life-threatening health complications, including cancer of the throat, mouth and lung. Lung cancer alone claimed the lives of more than 1.8 million people in 2020, making it the most dangerous disease. The main reason of cancer deaths worldwide.

Over the years, government agencies and activist groups have restricted Big Tobacco’s ability to reduce the number of smokers, provide resources to aspiring quitters, replace aforementioned Norman Rockwell-style advertising with alarmist images and health warnings, drive up cigarette prices, and limit tobacco sales to specialty stores.

However, the number of deaths due to lung cancer remains astronomically high. Fortunately, new and improved treatments for smoking-related diseases have made tremendous progress, with fields such as nanosurgery and immunotherapy injecting hope into a very disturbing topic. But no alternative treatment option has received the same level of attention as the lung cancer vaccine produced by the German biotechnology company BioNTech.

Drawing on technologies used to create coronavirus vaccinations, BioNTech launched its first clinical trial involving the new vaccine in August 2024. While the trials were praised by the media for their promise and potential, most of the coverage focused on the company’s soaring valuations, leaving many to wonder how the vaccine actually worked on a scientific level, why it arrived when it did, and when (if ever) a form of treatment would become widely available.

An injection of BioNTech mRNA cancer immunotherapy to treat non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) – known as BNT116 – at University College London Hospital. Approximately 130 study participants were enrolled across 34 research sites in seven countries, with six sites selected in the UK. Image date: Tuesday, August 20, 2024. (Aaron Chown/PA Images/Getty Images)

How it works

To understand how BioNTech’s lung cancer vaccine works, you first need to understand why we need a vaccine in the first place. While a functioning immune system can fight off a lot of nasty, potentially dangerous diseases, cancer cells—abnormal, ever-growing tissue—are unfortunately very adept at slipping under the system’s radar.

This is because cancer cells, in simple terms, are not external invaders but dysfunctional cells of the body, making it difficult for the immune system to recognize them as a threat. More specifically, small, newly formed cancer cells often lack these elements Strong antigens – Or they can suppress immune responses – allowing them to avoid detection. By the time they express recognizable antigens, tumors may have grown so large that the immune system cannot effectively eliminate them on its own.

This vision represents the starting point for immunotherapy, which – unlike chemotherapy or surgery – does not target cancer cells directly, but helps the immune system do its job more effectively.

Some immunotherapies are injected directly into the veins. Others come in the form of pills or creams. BioNTech is a vaccine. Specifically, it’s a vaccine that contains mRNA, or messenger-RNA, which can be loosely defined as the genetic blueprint for producing proteins. In this case: proteins that improve the immune system’s ability to find and kill tumors.

“The role of mRNA is to transfer protein information from the DNA in the cell nucleus to the cell’s cytoplasm (the aqueous interior).” Notes National Human Genome Research Institute, “The protein-making machinery reads the mRNA sequence and translates each three-base codon (sequences made up of the DNA molecules adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T)) into its corresponding amino acid in the growing protein chain.

A BioNTech spokesperson told Big Think that the vaccine is “designed to train the immune system to specifically recognize and attack cancer cells by delivering mRNA that encodes cancer-specific antigens, prompting the immune system to target those proteins made by cancer cells. This can help the body detect cancer cells, destroy them and potentially prevent them from coming back.”

Covid lessons

The BioNTech vaccine relies heavily on scientific advances made during the pandemic, which have led to the creation of vaccines that also use mRNA to help the immune system fight back. to set Specific goal. In this case: coronavirus.

Although mRNA was first discovered in 1961 (which earned researchers a Nobel Prize), University of Pennsylvania employees Katalin Carrico and Drew Weissman discovered how to use it in a vaccine as early as the 1990s, and its primary application at the time — fighting infectious diseases in Africa — was to fail To obtain sufficient financing from Western investors. Then of course came the coronavirus.

BioNTech has a long history of working with mRNA. During the pandemic, she participated in the development of the coronavirus vaccine distributed by the New York-based pharmaceutical company Pfizer, and discovered a mechanism capable of delivering genetic information to stem cells (a type of immune cell), which greatly improved the vaccine’s effectiveness and stability.

As clinical trials continue, BioNTech emphasizes that its vaccine is not currently intended to replace current treatments for late-stage lung cancer.

“In the early stage,” the company says. Big Think, “As the immune system may be more responsive to this approach because the tumor burden is lower, BNT116 (the official name of the vaccine) will likely be evaluated as a standalone treatment. However, it is generally designed to complement existing treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy or immunotherapy, to enhance the overall effectiveness of cancer treatment and reduce the risk of disease recurrence.”

When and whether BioNTech’s lung cancer vaccine becomes a widely available form of treatment depends on the results of the company’s ongoing clinical trials, which are currently being conducted at 34 research sites in 7 countries – including Germany and the UK – and include about 130 test subjects who receive one vaccine weekly for 6 consecutive weeks, followed by one vaccine every 3 weeks for 54 weeks.

The first person to receive the BioNTech vaccine, a 67-year-old Polish-born analyst named Janusz Racz, credits his profession with motivating him to join the trial. “As a scientist, I know that science can only advance if people agree to participate in programs like this,” he said in an article published by University College London Hospitals, where he is receiving treatment.

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ