Artificial Intelligence passes Turing tests. Don’t let that fool you either

By Tim Brinkhof | Published: 2024-12-09 16:20:00 | Source: High Culture – Big Think

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

In 1966, the famous American engineer A. Michael Knoll is a computer program capable of creating semi-random geometric compositions in the style of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, known for his abstract paintings such as Composition with red, blue and yellow and Broadway Boogie WoogieThe latter is intended to represent the bustling streets of Manhattan as seen from the top of a skyscraper. Mondrian’s work is often described as incomparable. But if this title applies to human imitators, it does not apply to their mechanical counterparts. In fact, when Knoll showed his test subjects’ images, only 28% of them could tell they weren’t made by a real person.

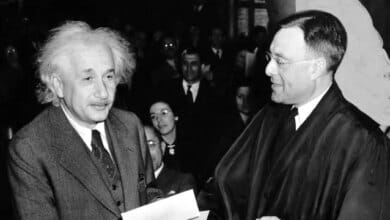

In robotics, this type of experiment is known as the Turing test. Named after the British mathematician Alan Turing, who developed one of the first modern computers to decode German intelligence during World War II, the goal of these tests is to see whether or not a machine or program can look like a human — and given the rapid development of AI tools like ChatGPT and Dall-E, to name just two, they will have to become more stringent if we are to distinguish between… Strictly art and algorithm.

At least, that’s what Moscow-born artist and author Lev Manovich argues Synthetic aesthetics: Generative AI, Art and Visual Media. The book was written alongside philosopher Emmanuel Arieli between 2021 and 2024 – Available to the public online Not only does it explain how machine learning produces art on a technical level, but it also teaches readers to recognize AI-generated images that a rudimentary Turing test would fail to detect.

Rembrandt and Mondrian versus Duchamp

Unlike professional artists, AI-powered text-to-image models create visual images based on what people find aesthetically pleasing. But while the former is based first and foremost on principles passed down through centuries of art history, the latter has access to a different and larger set of data, including the types of styles and themes that attract the most attention on social media.

“Previous predictions of image quality ratings were based on classic constructs, such as rule of thirds, aspect ratio, saturation, etc.,” Manovich and Ariely write. Nowadays, neural networks go even further, being able to “extract aesthetically relevant features by analyzing large databases of popular images.”

Thanks to these advances, computer programs now regularly pass the Turing test. Speaking to Big Think, Manovich points to Dutch advertising director Bas Corsten, whose algorithm – developed by data scientists from Microsoft and Delft University of Technology – was able to create a compelling image in the style of Rembrandt van Rijn Having been trained in all of the artist’s 346 known paintings, complete with his trademark use of light and shadow, expressive brushstrokes, and animated facial expressions. In 2020, a Princeton undergraduate accomplished the same thing, but using traditional Chinese landscape painting.

But artificial intelligence isn’t just about passing Turing tests for the visual arts. DeepBach, a neural network developed by Sony Computer Science Laboratories in Paris, can compose chorale cantatas that music historians consider almost identical to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Creative writing is also being invaded by artificial intelligence. About the heroa documentary about a murder mystery that premiered this fall, based on the work of German director Werner Herzog, was met with rave reviews, although Herzog Own doubt.

As impressive as these cases seem, Manovich insists that their implications should be taken with caution. His work is limited to the world of visual art, and he points out that some artistic styles are easier for artificial intelligence to imitate than others. While a human painter would need years if not decades of training before he could produce paintings as lifelike as those of Rembrandt or Leonardo da Vinci, machine learning can achieve the same level of artistic mastery in a matter of seconds. Not because it’s easy, but because it relies on the kinds of rules and patterns that machine learning excels at identifying and applying.

“Clearly recognizable patterns represent well-defined problems that can be reduced to computational tasks,” says Maniewicz. It is interesting that the artists are the ones no Following a clearly recognizable set of rules or patterns, like Marcel Duchamp or Andy Warhol, which AI struggles to effectively imitate. And again, not because their art is abstract—and neither is Mondrian’s art—but because their ever-evolving methods, use of mixed media, and cerebral concepts lead to “non-specific tasks that have no easy procedural solution.”

As Maniewicz and Ariely wrote Synthetic aesthetics“The common clichés directed at contemporary art (specifically, ‘My kid could have done that!’) now seem, in an ironic reversal, to turn against the great, stylistically complex—but computationally scalable—art of the cultural tradition: even artificial intelligence can do it. It is Duchamp who remains outside the creative powers of artificial intelligence, at least in “Current time.”

Turing test

Although AI-generated images are skilled at turning them into human-made works of art, there are a number of ways you can recognize them. Aside from artistic styles that are easier to imitate than others, different generations of machine learning tools tend to have a common aesthetic.

“Obviously we’re talking about a moving target, but historically, new media tends to take a distinct look at it, like early cinema from the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” Manovich tells Big Think. Currently, a lot of AI-generated art features symmetrical compositions, with the object of interest in the middle — very different from what you find in classical or contemporary art. “Man-made.”

Some other common characteristics of AI-generated art include intricate detail, high resolution, and borderline surreal, indistinguishable backgrounds — in short, the kind of rule-based visual information that algorithms are best suited to come up with.

Less common in AI-generated art is visual information that is not necessarily rule-based, or relies on rules that cannot be easily extracted from ones and zeros, such as the intentional distortion of an object’s shape and color to elicit a specific emotional response in the viewer, or the insertion of a self-referential message or idea in the context of Duchamp’s 1917 signed urinal, “The Fountain,” which is not related to the work Himself as far as what he says. About the history and culture of world art.

Aside from its practical applications, the ability to distinguish AI art from its real human counterpart through more stringent Turing tests raises questions about the nature of creativity. Simply put: If people can’t tell whether a particular image was created by a person or a program, what does that say about the value of a computer-generated image?

Manovich, for example, does not believe that artificial intelligence heralds the end of art history. He believes that the effects of technology act as a logical continuation of art produced during the twentieth century.

“In modern art,” he says, “artists often rejected the idea of exercising complete and comprehensive control over their work. They saw the machines and materials they used as an integral part of their creative process. Andy Warhol, for example, photographed the Empire State Building for hours, refusing to interfere with the shots. Others used automatic writing or random number generators. This tradition of “In using structures and systems with AI-generated art, which also challenges the idea that art has no value unless created by a human.”

“Indeed, in the early days of digital art, artists used algorithms and random numbers, making their work perhaps more ‘machine-like’ than today’s AI, which we control by selecting training data and formulating prompts. The current form of AI is more directive, which means it can be viewed as a collaborative tool rather than pure machine art,” he adds.

If artistic collaboration becomes human and artificial intelligence becomes ubiquitous, we may collectively choose to abandon the task of trying to discern who made a piece of art. Perhaps it is simply too boring: “…the impossibility of true identification may lead to a ‘post-artificial’ position, (…) where we ultimately suspend judgment on the true authorial origin of the work, permanently abandoning the question of whether something is truly ‘human-made’ or not.”

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week for free.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ